Case study: Seasonal dynamics of flood-plain forests

The overall condition of a plant or an entire ecosystem is often assessed by its chlorophyll content. To be able to obtain or validate absolute values of chlorophyll content from remote sensing data, reliable ground truth data sets are needed. Non-destructive measurements, such as various portable chlorophyll meters, are often used as ground truth data in remote sensing studies.

Objectives

The objectives of this case study are as follows:

-

To estimate the accuracy of chlorophyll content measured by the portable transmittance-based chlorophyll meter SPAD-502 by comparison with a laboratory reference.

-

To compute chlorophyll indices based on spectra measured by the spectroradiometer ASD FieldSpec4 Standard-Res coupled with an integrating sphere; to build and validate empirical models between indices and chlorophyll content.

-

To compare the performance of empirical models using data from the entire vegetation season and data from one term.

The case study will be presented on a dataset from a floodplain forest in Czechia where all the measurements were conducted on the set of various deciduous trees during the vegetation periods of 2019 and 2020.

Data

The dataset (module4/case_study_flood_plain_forests) was acquired in the Soutok floodplain forest district located between the rivers Morava and Dyje (48.68° N, 16.94° E) in 2019 (four field campaigns conducted in April, July, September, and October; 204 samples) and 2020 (three field campaigns in May, July, ans October; 193 samples). During each field campaign, sunlit and shaded branches were trimmed from eighteen deciduous trees of six species: Austrian oak, English oak, Narrow-leaved ash, European hornbeam, White poplar and Small-leaved linden (Figure 1). Representative leaves of all types (small, large, green, colored, young, old) were measured using the chlorophyll meter SPAD-502 and the ASD FieldSpec4 Standard-Res spectroradiometer (350 – 2,500 nm sampling spectral domain) coupled with the integrating sphere RTS-3ZC. The leaves were then taken to the laboratory for spectrophotometric determination of chlorophyll content from dimethylformamide extracts (Figure 2). Data from 2019 will be used for training purposes, and data from 2020 will serve as validation of the results.

Input data file FloodplainForest_input_data.xlsx consists of two sheets: 2019_training and 2020_validation. Data is also available in the form of text files separated by a tabulator for work in R (FloodplainForest_2019_training.txt and FloodplainForest_2020_validation.txt). All the files have the same columns:

CampNo_year– field campaign number (1 to 7) and year (19 for 2019, 20 for 2020)Month– month on acquisitionSpecies– tree speciesTreeNo– number of sampled treeID_Biochem– ID of leaf used for chlorophyll measurementSPAD_Cab– SPAD value correlating with content of chlorophyll a+bTotal_chloro_ug_cm2– total chlorophyll content in μg/cm² extracted in laboratory (further in text referred to as laboratory chlorophyll content)350 – 2500– reflectance at a given wavelength measured by the spectroradiometer

Figure 1. Map of the study area showing the location of 18 sampled trees; aerial hyperspectral CASI data in the background.

Figure 2. Examples of sampled leaves in October 2020 (up), field laboratory (down).

Chlorophyll meter vs. laboratory chlorophyll content

To begin, consider the relationship between both methods of determining chlorophyll content and seasonal changes in chlorophyll content.

By building simple regressions (table editor: XY point graph / add trendline or R: lm(SPAD_Cab ~ Total_chloro_ug_cm²)) for each month

(April 2019, May 2020, July 2019, July 2020, September 2019, October 2019, October 2020) and year (2019, 2020), we can see how the two values are correlated and how the chlorophyll content and the correlation values change over the seasons (Figure 3).

At the start of the season, data variability is so low that the correlation fails (April 2019, R² = 0.04).

In May, the correlation becomes stronger, which is consistent with some studies that have looked for the most appropriate term to distinguish between different deciduous tree species.

Lisein et al., 2015; Grybas and Congalton, 2021 discovered that the end of May is ideal as on species' phenology is well synchronized but inter-species differences are still visible.

Our result (R² = 0.8) is influenced by two outliers, but when they are removed, the correlation remains very strong R² = 0.73 (not shown in Figure 3).

The correlations are weaker in July (July 2019 – R² = 0.50, July 2020 – R² = 0.70) as all the species are at their phenology peak.

A similar trend can be observed in September 2019 (R² = 0.72, not shown in Figure 3).

When the leaves begin to change color in the autumn, the variability in chlorophyll content in different species and leaves increases, and correlations improve (October 2019 – R² = 0.82, October 2020 – R² = 0.87).

Autumn is another term that is frequently used to distinguish deciduous trees. The best results are obtained by incorporating all of the months (R² for 2019 = 0.86 and for 2020 = 0.87), but the trend is no longer linear.

Figure 3. Correlation between SPAD values and laboratory chlorophyll content in different time periods.

Empirical modeling

There are numerous indices for estimating chlorophyll content of vegetation.

Most of the indices can be found in the remotes sensing Index DataBase or in various articles,

e.g. comparison of indices for estimating chlorophyll content were made by Main et al., 2011; Croft et al., 2014; le Maire et al., 2008, vegetation changes were evaluated using indices by Mišurec et al., 2016.

It is usually a good idea to compute as many indices as feasible to discover the optimal correlation. In this case, we created a script in R to compute thirty indices based on spectroradiometer data

and to construct simple linear regressions between indices and laboratory chlorophyll content, respectively SPAD values (Code 1).

To begin, run the script for data from the entire season 2019 (shown in Code 1, download) and then for data from individual months in 2019.

The results are shown in Figure 4. The majority of the models were statistically significant, with more non-significant models discovered only in April (with only 36 samples).

Based on the data from April, it can also be seen that the coefficients of determination are extremely low, particularly for regression of indices and laboratory chlorophyll content.

For SPAD values, slightly better results were achieved, which could be attributed to the method of measuring chlorophyll content by SPAD-502.

Transmittance is measured at two wavelengths (650 and 940 nm), which are similar to wavelengths used for computing the vegetation indices.

As the season progresses, the regression becomes stronger, because dataset variability increases and more samples are collected (46 in July, 56 in September, and 66 in October).

The October dataset and datasets containing data from the entire season yield the best results.

Compute thirty indices and linear regressions for data from the entire season of 2019 with the following code in R (Code 1):

data=read.delim("FloodplainForest_2019_training.txt") # load data

fix(data) # view data

attach(data)

# Chlorophyll content indices

# Main et al. 2011

MCARI=((X700-X670)-0.2*(X700-X550))*(X700/X670) # (Main et al. 2011; Daughtry et al. 2000)

MCARI2=((X750-X705)-0.2*(X750-X550))*(X750/X705) # (Main et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2008)

TCARI=3*((X700-X670)-0.2*(X700-X550)*(X700/X670)) # (Main et al. 2011; Haboudane et al. 2002)

OSAVI=(1+0.16)*(X800-X670)/(X800+X670+0.16) # (Main et al. 2011; Rondeaux et al 1996)

OSAVI2=(1+0.16)*(X750-X705)/(X750+X705+0.16) # (Main et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2008)

TCARIOSAVI=TCARI/OSAVI # (Main et al. 2011; Haboudane et al. 2002)

MCARIOSAVI=MCARI/OSAVI # (Main et al. 2011; Daughtry et al. 2000)

MCARI2OSAVI2=MCARI2/OSAVI2 # (Main et al. 2011; Wu et al. 2008)

TVI=0.5*(120*(X750-X550)-200*(X670-X550)) # (Main et al. 2011; Broge and Leblanc 2000)

MTCI=(X754-X709)/(X709-X681) # (Main et al. 2011; Dash and Curran 2004)

mND705=(X750-X705)/(X750+X705-2*X445) # (Main et al. 2011; Sims and Gamon 2002)

Gitelson2=(X750-X800/X695-X740)-1 # (Main et al. 2011; Gitelson et al. 2003)

Maccioni=(X780-X710)/(X780-X680) # (Main et al. 2011; Maccioni et al. 2001)

Vogelmann=X740/X720 # (Main et al. 2011; Vogelmann et al. 1993)

Vogelmann2=(X734-X747)/(X715+X726) # (Main et al. 2011; Vogelmann et al. 1993)

Datt=(X850-X710)/(X850-X680) # (Main et al. 2011; Datt 1999)

Datt2=X850/X710 # (Main et al. 2011; Datt 1999)

SR1=X750/X710 # (Main et al. 2011; Zarco-Tejada and Miller 1999)

SR2=X440/X690 # (Main et al. 2011;Lichtenthaler et al. 1996)

DD=(X749-X720)-(X701-X672) # (Main et al. 2011; le Maire et al. 2004)

Carter=X695/X420 # (Main et al. 2011; Carter 1994)

Carter2=X710/X760 # (Main et al. 2011; Carter 1994)

REP_LI=700+40*((X670+X780/2)/(X740-X700)) # (Main et al. 2011; Guyot and Baret 1988)

# Misurec et al. 2016

REP=700+40*((((X670+X780)/2)-X700)/(X740-X700)) # (Misurec 2016; Curran et al 1995)

RDVI=(X800-X670)/sqrt(X800+X670) # (Misurec 2016; Roujean and Breon 1995)

MSR=((800-670)-1)/sqrt((X800/X670)+1) # (Misurec 2016; Chen 1996 )

MSAVI=0.5*((2*X800+1-sqrt((X800+1)^(2))-8*(X800-X670))) # (Misurec 2016; Qi et al. 1994)

N705=(X705-X675)/(X750-X670) # (Misurec 2016; Campbell et al. 2004)

N715=(X715-X675)/(X750-X670) # (Misurec 2016; Campbell et al. 2004)

N725=(X725-X675)/(X750-X670) # (Misurec 2016; Campbell et al. 2004)

# add indices to the original table

dataVI=(cbind(data,MCARI,MCARI2,TCARI,OSAVI,OSAVI2,TCARIOSAVI,MCARIOSAVI,MCARI2OSAVI2,TVI,MTCI,mND705,Gitelson2,Maccioni,Vogelmann,Vogelmann2,Datt,Datt2,SR1,SR2,DD,Carter,Carter2,REP_LI,REP,RDVI,MSR,MSAVI,

N705,N715,N725))

write.table(dataVI,"FloodplainForest_2019_training_indices.txt") # save data and indices to the text file

fix(dataVI) # view data + indices

# explore the dimensions of the original table and table with indices; next a for loop will be computed only for indices, i. e. from the number of columns of the original data +1 till the end

dim(data)

dim(dataVI)

# create empty vectors

results_p <- vector()

results_R <- vector()

results_i <- vector()

results_koef <- vector()

# compute linear regression model between indices and laboratory chlorophyll content in a for loop and saving the p-values, coeficient of determination and equation coefficients to the text files

for (I in 2159:2188) # change the values of I based on the results of dim function

{

model<-lm(dataVI$Total_chloro_ug_cm2~dataVI[,I]);

sum=summary(model)

out<-capture.output(sum);

results_p <- append(results_p,grep ("p-value", out, value = TRUE) );

results_R <- append(results_R,grep ("Multiple R-squared", out, value = TRUE) );

results_i <- append(results_i,grep ("(Intercept)", out, value = TRUE) );

results_koef <- append(results_koef,grep ("dataVI", out, value = TRUE) );

}

write(results_p, "2019_Tot_chl_results_p.txt")

write(results_R, "2019_Tot_chl_results_R.txt")

write(results_i, "2019_Tot_chl_results_i.txt")

write(results_koef, "2019_Tot_chl_results_koef.txt")

# the same loop for SPAD values

results_p <- vector()

results_R <- vector()

results_i <- vector()

results_koef <- vector()

for (I in 2159:2188) # change the values of I based on the results of dim function

{

model<-lm(dataVI$SPAD_Cab~dataVI[,I]);

sum=summary(model)

out<-capture.output(sum);

results_p <- append(results_p,grep ("p-value", out, value = TRUE) );

results_R <- append(results_R,grep ("Multiple R-squared", out, value = TRUE) );

results_i <- append(results_i,grep ("(Intercept)", out, value = TRUE) );

results_koef <- append(results_koef,grep ("dataVI", out, value = TRUE) );

}

write(results_p, "2019_SPAD_Cab_results_p.txt")

write(results_R, "2019_SPAD_Cab_results_R.txt")

write(results_i, "2019_SPAD_Cab_results_i.txt")

write(results_koef, "2019_SPAD_Cab_results_koef.txt")

Figure 4. Coefficient of determination (R²) for linear regression between SPAD values (upper table) resp. laboratory chlorophyll content (lower table) and thirty vegetation indices based on datasets from April, July, September, October and the whole season of 2019. Red means the worst models, green the best.

Because the dataset for the entire season includes all potential chlorophyll values, the regression equations should be able to estimate chlorophyll content based on the indices from different seasons.

Let’s compute the indices for the 2020 validation dataset, and based on the regression equations from 2019, estimate the SPAD values and laboratory chlorophyll content for the best performing indices, i.e. for SPAD value – N705 (R² = 0.8566, SPAD_value = -61.215 * N705 + 55.688) and for laboratory chlorophyll content – Vogelmann (R² = 0.809, Lab_Chlorophyll = 88.635 * Vogelmann - 84.965).

The intercept can be found in script output text files ending with _i and slope values can be found in script output text files ending with _koef. For more details, see Figure 5.

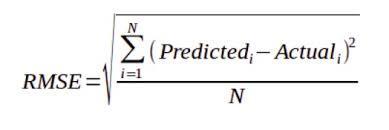

Then, let’s compare the actual and predicted values using graphs (Figure 6) and the computing root mean square error (RMSE), which measures the average difference between a statistical model’s predicted and actual values (Formula 1).

Figure 5. Results of regression model for laboratory chlorophyll content and Vogelmann index with highlighted intercept and slope values.

Figure 6. Actual vs. predicted values of laboratory chlorophyll content (left) and SPAD values (right), 2020 dataset.

RMSE for predicted laboratory chlorophyll content was 6.6 μg/cm² (average of 2020 validation dataset was 31.9 μg/cm² and standard deviation 15.2 μg/cm2), for predicted SPAD values 4.9 μg/cm² (average of 2020 validation dataset was 31.9 and standard deviation 11.3). It can be seen that computed regressions for both indices and parameters also perform well for other seasons.

Conclusions

In the first part of the case study, we explored the relation between two methods of chlorophyll content determination – destructive (total chlorophyll content extracted in laboratory) and non-destructive (measured by the portable transmittance-based chlorophyll meter SPAD-502). We found out that if there is enough variability in data, the correlation between these two methods of chlorophyll content determination works well. The time-demanding and destructive method of chlorophyll content extraction in the laboratory can be substituted by fast non-destructive measurements, and prediction equations can be used to obtain total chlorophyll content in μg/cm². But these equations are not transferable to different ecosystems with potentially different chlorophyll content values. Each ecosystem requires new calibration.

In the second part of the case study, we explored the correlation of vegetation indices computed from spectra measured by the spectroradiometer coupled with the integrating sphere and the chlorophyll content values. The best performing indices were Vogelmann for laboratory chlorophyll content and N705 for SPAD values. Equations developed using data from the entire season of 2019 were successfully applied to the 2020 dataset (RMSE validation). Slightly better performance was reached for predicting SPAD values from the indices, which can be caused by similar methods of chlorophyll content estimation (both optical measurements). These findings confirm that spectroradiometer measurements of leaf reflectance are promising method for estimating chlorophyll content in leaves.

Seasonal changes were also taken into account. When working with the entire season's dataset, all possible chlorophyll content values for the specific ecosystem were considered, and the strongest models were produced. However, this required a significant amount of field work. For a floodplain forest, October could be recommended as a suitable month to conduct a similar study. The variability in leaves is high, and the models perform accordingly.

References

Croft, H., J.M. Chen, & Y. Zhang. 2014. „The Applicability of Empirical Vegetation Indices for Determining Leaf Chlorophyll Content over Different Leaf and Canopy Structures". Ecological Complexity 17 (March): 119–30. 10.1016/j.ecocom.2013.11.005.

Grybas, H., & Congalton, R. G. 2021. A comparison of multi-temporal rgb and multispectral uas imagery for tree species classification in heterogeneous new hampshire forests. Remote Sensing, 13 (13). 10.3390/rs13132631.

Lisein, J., Michez, A., Claessens, H., & Lejeune, P. 2015. Discrimination of deciduous tree species from time series of unmanned aerial system imagery. PLoS ONE, 10 (11). 10.1371/journal.pone.0141006.

Main, Russell, Moses Azong Cho, Renaud Mathieu, Martha M. O’Kennedy, Abel Ramoelo, & Susan Koch. 2011. „An Investigation into Robust Spectral Indices for Leaf Chlorophyll Estimation". ISPRS Journal of Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing 66 (6): 751–61. 10.1016/j.isprsjprs.2011.08.001.

Maire, G. le, C. François, & E. Dufrêne. 2004. „Towards Universal Broad Leaf Chlorophyll Indices Using PROSPECT Simulated Database and Hyperspectral Reflectance Measurements". Remote Sensing of Environment 89 (1): 1–28. 10.1016/j.rse.2003.09.004.

Mišurec, Jan, Veronika Kopačková, Zuzana Lhotáková, Petya Campbell, & Jana Albrechtová. 2016. „Detection of Spatio-Temporal Changes of Norway Spruce Forest Stands in Ore Mountains Using Landsat Time Series and Airborne Hyperspectral Imagery". Remote Sensing 8 (2): 92. 10.3390/rs8020092.

Back to the start

Proceed by returning to module overview